Women’s Health & The Dangers of Inactivity Across the Lifespan

It has only been in the past few decades that we have really started examining why exercise is vital for women’s health. Our exercise habits play a huge role in determining our overall health in all stages of life, particularly during periods of hormonal change (such as menopause). Factoring in exercise will not only lead to improved health, better chronic disease prevention and management, but will set us in good stead to deal with everyday demands and be better for ourselves and those around us. Today, Longevity Exercise Physiology Drummoyne, Edgecliff, Marrickville, Castle Hill, Randwick, Pymble, Kingsgrove, Neutral Bay and Coburg would like to discuss the dangers of inactivity for women across the lifespan.

How many women meet the Australian Physical Activity Guidelines?

The Australian Physical Activity Guidelines recommend every Australian 18-64 years old engage in 150-300 minutes of moderate intensity or 75-150 minutes of vigorous intensity aerobic activity plus two sessions of muscle-strengthening activities per week.

For those 65 years and older, the guidelines recommend 30 minutes of moderate intensity physical activity on most, if not all days.

Only 2 in 5 women met these guidelines in 2017-18 (AIHW, 2019). These statistics also revealed that as women age, they become less active. While 1 in 2 women aged 18-64 were sufficiently active, this reduced to 1 in 4 women over 65 years (ABS, 2019).

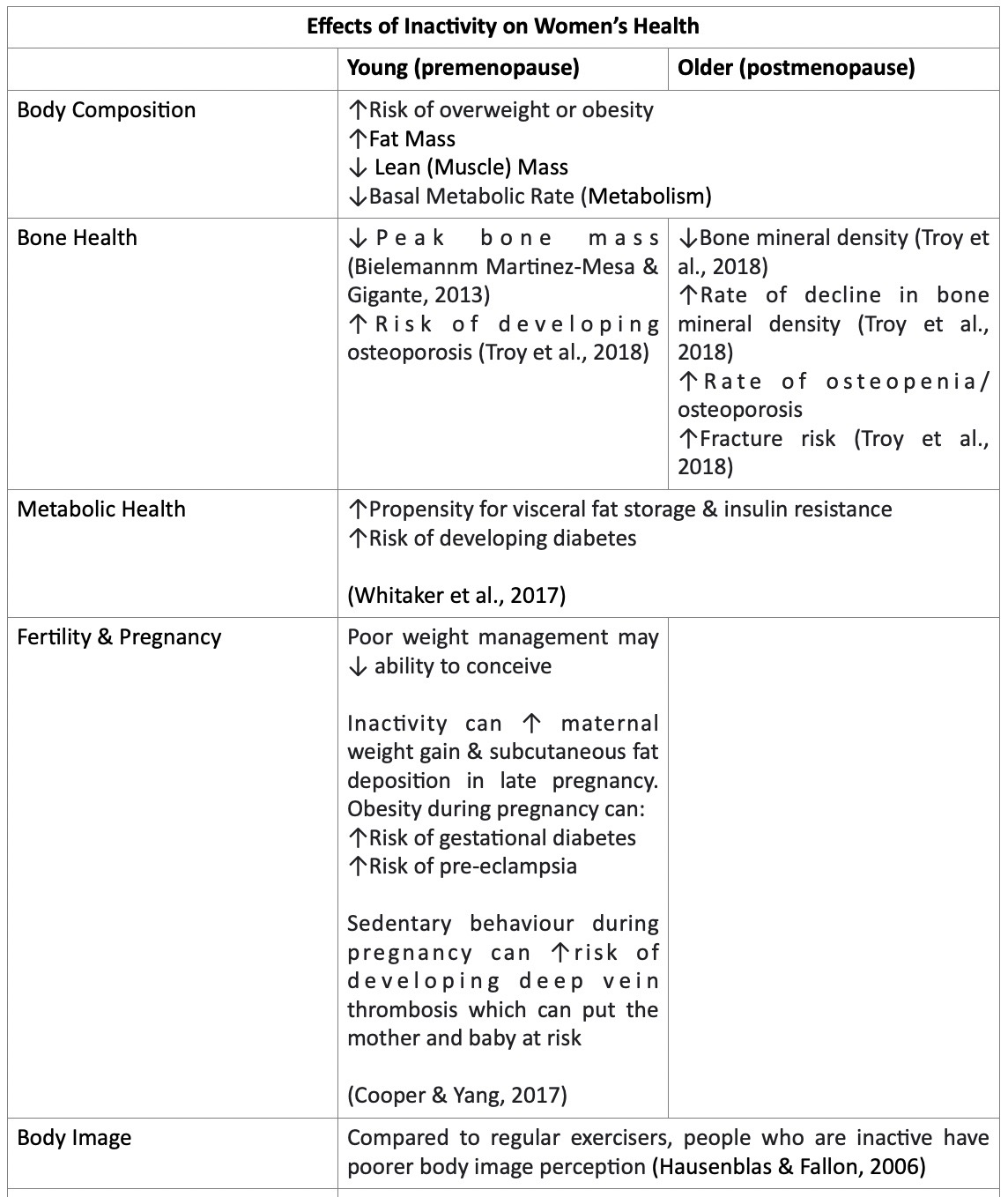

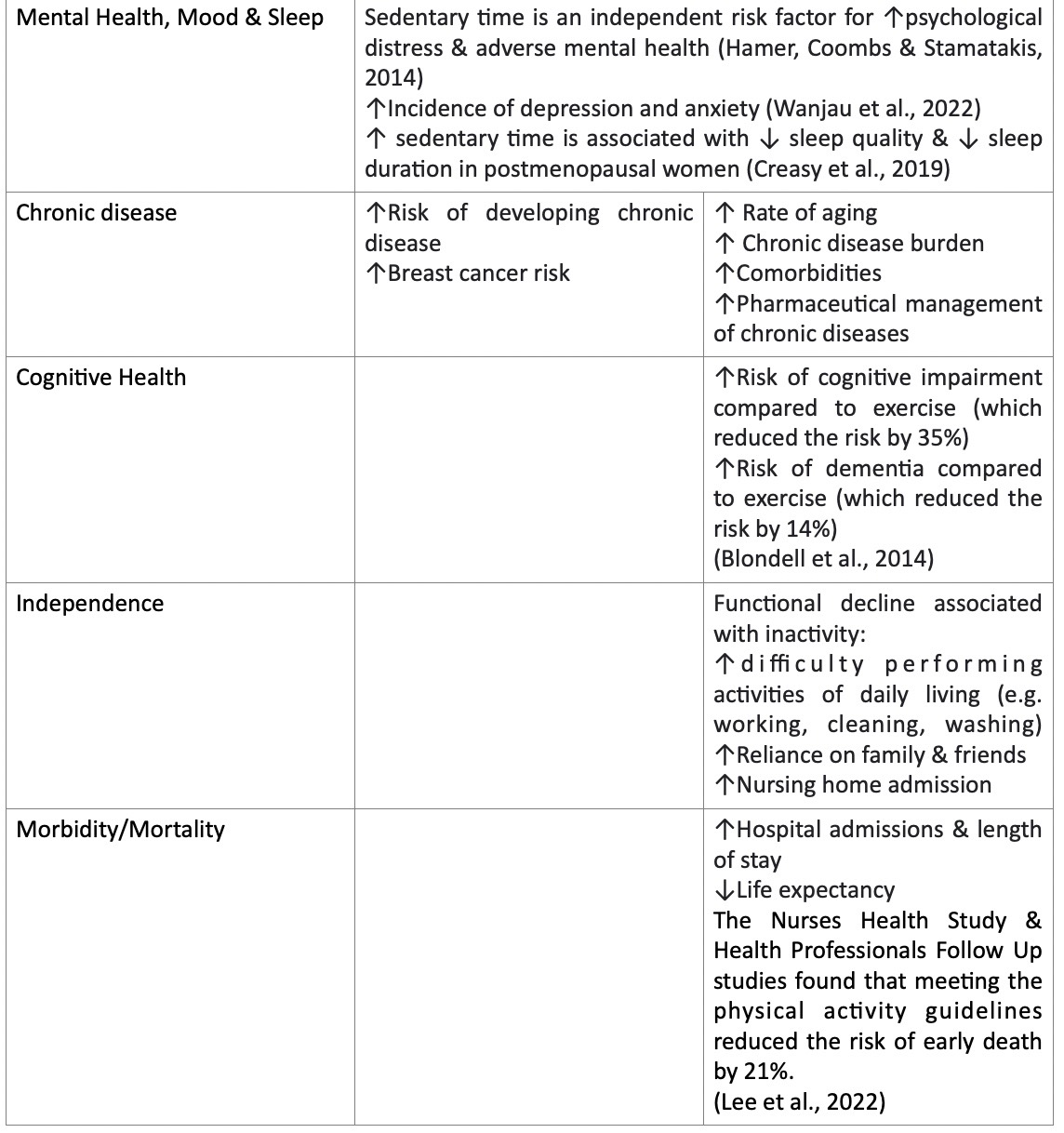

The effect of inactivity on women’s health:

There are many compelling reasons for women to start exercising.

For young or premenopausal women, exercise is an effective way to future-proof our bodies to fight the effects of ageing, including managing risk factors associated with the development of chronic disease. For those considering becoming pregnant or who are already pregnant, being active and maintaining a healthy weight can help you conceive and can improve outcomes for you and your baby.

“…For premenopausal women, exercise is an effective way to future-proof our bodies to fight the effects of ageing.”

Older, postmenopausal women exercise less than their younger counterparts. As an exercise professional this is concerning because the changes during menopause leave women more vulnerable to the effects of ageing and chronic diseases such as osteoporosis, metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease. Age is not a reason not to exercise.

The table below summarises the reasons why women of all ages should avoid inactivity.

The evidence points strongly towards exercise as benefiting the health of young and not-so-young women. The decision to exercise regularly has both short and long-term effects- it all comes down to behaviour change, making activity a priority & developing a good relationship with exercise.

How can I get started with exercise if I’m scared to go to a gym?

It is very common, particularly for women, to say they are apprehensive about going to the gym. The weights area particularly can feel like a ‘boys’ club and a lot of women confine themselves to the cardio equipment or choose not to go at all.

While going to the gym is a great way to start your exercise journey, there some simple ways to get started.

- Start small. For people who are very inactive, small increases in activity can make huge differences. Depending on your current activity, start by walking as little as 10 minutes per day and slowly build up to 30 minutes. Try to increase the intensity of the walk by factoring in stairs, hills and increasing your walking speed.

- Find an ‘exercise buddy’ to keep you accountable to your goals & exercise together. Evidence shows that accountability to another person dramatically increases adherence to exercise.

- See an Exercise Physiologist. We are health professionals who specialise in the prescription of exercise for the prevention, management, and treatment of chronic disease. We can help you exercise in a safe space, with an individualised program tailored to your health conditions, exercise goals & preferences. If you have a chronic condition or are looking at prevention, seeing an Exercise Physiologist is the safest and most effective way to start exercise, help you change your behaviour and reach your goals.

Give Longevity Exercise Physiology a call today on 1300 964 002 to book in with an Exercise Physiologist to help you get started on your exercise journey.

References

Bielemann, R. M., Martinez-Mesa, J., & Gigante, D. P. (2013). Physical activity during life course and bone mass: a systematic review of methods and findings from cohort studies with young adults. BMC musculoskeletal disorders, 14, 1-16.

Blondell, S. J., Hammersley-Mather, R., & Veerman, J. L. (2014). Does physical activity prevent cognitive decline and dementia?: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. BMC public health, 14(1), 1-12.

Cooper, D. B., & Yang, L. (2017). Pregnancy And Exercise.

Creasy, S. A., Crane, T. E., Garcia, D. O., Thomson, C. A., Kohler, L. N., Wertheim, B. C., … & Melanson, E. L. (2019). Higher amounts of sedentary time are associated with short sleep duration and poor sleep quality in postmenopausal women. Sleep, 42(7), zsz093.

Hamer M, Coombs N, Stamatakis E. Associations between objectively assessed and self reported sedentary time with mental health in adults: an analysis of data from the Health Survey for England. BMJOpen2014;4:e004580. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2013004580

Hausenblas, H. A., & Fallon, E. A. (2006). Exercise and body image: A meta-analysis. Psychology and health, 21(1), 33-47.

Heaney, R. P., Abrams, S., Dawson-Hughes, B., Looker, A., Marcus, R., Matkovic, V., & Weaver, C. (2000). Peak bone mass. Osteoporosis international, 11(12), 985.

Pinheiro, M. B., Oliveira, J., Bauman, A., Fairhall, N., Kwok, W., & Sherrington, C. (2020). Evidence on physical activity and osteoporosis prevention for people aged 65+ years: a systematic review to inform the WHO guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 17(1), 1-53.

Wanjau, M. N., Möller, H., Haigh, F., Milat, A., Hayek, R., Peta, L., & Veerman, J. L. (2022). Physical activity and depression and anxiety disorders in Australia: a lifetable analysis. AJPM Focus, 100030.

Whitaker, K. M., Pereira, M. A., Jacobs Jr, D. R., Sidney, S., & Odegaard, A. O. (2017). Sedentary behavior, physical activity, and abdominal adipose tissue deposition. Medicine and science in sports and exercise, 49(3), 450.